- Home

- Glenn Bryant

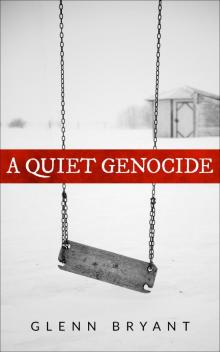

A Quiet Genocide

A Quiet Genocide Read online

A Quiet Genocide

The Untold Holocaust of Disabled Children in WW2 Germany

Glenn Bryant

Copyright © Glenn Bryant, 2018

ISBN 13: 9789492371836 (ebook)

ISBN 13: 9789492371829 (paperback)

Publisher: Amsterdam Publishers, the Netherlands

[email protected]

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

About the Author

Further Reading

For Juliet Robson, a UK artist whose work and spirit inspired this story

‘We have broken the laws of natural selection. We have supported unworthy life forms and we have allowed them to breed.’ (Adolf Hitler, 1925)

Chapter One

Breakfast was business-like in the Diederich household. Catharina asked Gerhard what time he would be home from work and what he would prefer for supper. Gerhard was polite and accommodating in response, but cradling a hangover the size of a U-boat he was in no mood to upset. He was a skilled man from the upper working class and he had married above his modest station when he and Catharina had fallen in love at a dance in Munich in the summer of 1929. Twenty-five winters had passed since. It had been a quick courtship and they had wed in December that year. Catharina’s father was a casualty of the Great War and her once comfortable family were on hard times. Gerhard had steady work in interwar Germany, which few peers did, and even though Catharina’s mother was fighting disappointed tears on their wedding day – a cold but clear day – in the circumstances he was a decent match, dependable.

Catharina had taken odd jobs but she had never consistently worked. The soft hands she used to stroke the face of Jozef, their only child, revealed as much. She ran a good house, she was a dutiful wife, she was a doting mother and she was stunning. But age was starting to creep up on her, invisible like the tide, which alarmed her if she ever caught her reflection in a weak moment.

Catharina’s friends from her youth and their strictly middle-class husbands peered down on Gerhard, as if they were removing their reading glasses reproachfully before bringing him sharply into focus. They were all doing worse when it came to money in their pockets, but, perversely, rampant inflation and an economic crash had only made them cling more stubbornly to their status and increased the number of jibes.

Tonight, Gerhard and Catharina were hosting the parents of their son’s closest friend, Sebastian, for dinner. Gerhard was drained from drinking the previous night and he really did not care to, but Catharina maintained it was good etiquette given the fact that their sons spent so much time together. Sebastian’s parents, Karl and Jana, enjoyed these occasions more, but only when they entertained. Jana was a much better cook than Catharina, who knew it.

A warm knock at the front door. Karl and Jana.

Jozef was quickest and paced down the Diederich’s narrow hallway. He opened the door into darkness and rain and, more happily, Karl and Jana and Sebastian smiling.

‘Jozef!’ said Jana. ‘How handsome you look.’

‘Thank you Frau Gottlieb,’ he replied.

‘Jana, please Jozef,’ said Jana, briefly touching his hair.

Jozef’s mother walked up the hallway, wiping her wet hands on a tea towel. ‘Jana, how are you?’ she said kindly, brushing over any discomfort between them and wondering why they did not have the Gottliebs over more often. She liked it. It was sociable. It was pleasant.

The two women kissed each other tenderly on the cheek.

‘Gerhard,’ said Karl more formally, shaking Gerhard’s hand through the crowd. ‘Come through, come through,’ he said, desperately trying to perk himself up. Tonight felt like completing back-to-back shifts in the office. He had to be on duty. A drink would help dull that depression, he thought. ‘Let me take your coats,’ he said, heaping them up on overcrowded hooks in the hallway.

‘What can I get you both to drink?’ asked his wife. ‘Wine? We only have red I’m afraid but you can have whisky with Gerhard if you prefer, Karl.’

‘Wine will be perfect,’ said Karl.

‘We only drink red anyway,’ added Jana, lying politely.

Karl, Jana and Gerhard filled the Diederich’s front room, tidied immaculately by Catharina earlier in the day.

Gerhard noticed the effort she had made. He remained in a dated brown work suit but he had removed his tie, while Karl wore an elegant crisp white shirt with two buttons undone at the top. It was clear he was still slim, desirable. Jana was in a beautiful, sweeping blue dress, cut confidently above her calves, and high heels, which she playfully removed. Gerhard could not help peeking at her shapely legs and neat feet with painted toenails when she did so. Jana did not notice. Karl didn’t miss the moment, but let it pass.

The wine and whisky worked kindly, softening the atmosphere while candlelight flattered people’s flaws with its flicker.

With Catharina in and out of the room completing final preparations for dinner, talk turned to the war and twelve years of National Socialist rule in Germany.

‘I was never that enthusiastic about that moustache,’ said Jana, half smiling until she saw no one was replying in kind.

‘I remember once paying four million Deutsche Marks for sausages and bread,’ Karl said quickly to save his wife’s dignity. ‘I think we all thought democracy had failed.’

Gerhard was more drunk than anyone else in the room. Intoxication started to loosen his tongue. He was aroused by Jana’s presence at their table.

Catharina had not realised what state he was in, but she knew her husband was drinking quickly and she tensed every time he opened his mouth, fearing what might fall out.

‘Brutality is respected in this world,’ he said too casually for comfort. ‘People needed something to fear. They wanted to be frightened.’

‘You sound like you miss him,’ teased Jana, trying to make light of his stance.

‘There was enormous poverty at the time,’ said Catharina quickly and uncharacteristically, because she nearly always hid her true thoughts. ‘But what I think really helped Hitler was the way French soldiers humiliated people.’

Karl nodded in agreement and Catharina was eternally grateful and breathed more easily again. Karl was sipping red wine and enjoying the main course of steak and boiled potatoes. His steak was dry, but it was a good cut of meat and he was touched by the expense Catharina had gone to.

‘I remember French troops beating people for using the pavement,’ he said. ‘They used riding crops.’

Karl heard one of the boys fall with a thud upstairs, followed by guilty giggles.

‘Boys?’ called Jana loudly over her shoulder.

‘Yes, mother,’ answered Sebastian.

‘Settle down.’

‘Yes, Frau Gottlieb,’ said Jozef.

‘Call me Jana, please.’

Gerhard winced at her last statement. It was too liberal for his conservative tastes and he immediately cooled.

‘I disliked Hitler when he spoke,’ said Catharina, delighted disaster had so far been averted. ‘He was always shouting.’

‘He was observing me,’ said Gerhard, who had a drunken distance fixed on his face.

‘Have you both finished?’ Catharina quickly turned to her guests, desperate to cut her husband off. She rose impatiently to her feet.

‘Yes, we have,’ said Jana, sensing something was wrong. ‘It was lovely – truly. We haven’t had steak for so long. It was a wonderful treat.’

I bet you have steak every night, you stupid cow, thought Gerhard.

Catharina smiled unconvincingly and carried the plates through to the kitchen.

Gerhard began again, ‘He was observing me. I felt his eyes resting on me. It was the most curious moment of my life.’

‘You met Hitler?’ said Jana, incredulous.

‘Yes,’ said Gerhard, refocusing on reality and the people around him. ‘At a rally in Nuremberg in 1933. I was with our friend Michael, who you might remember arranged for us to adopt Jozef.’

Karl and Jana knew Jozef was adopted, but any mention of it made them uneasy and they held their tongues, waiting for Gerhard to finish and be done with the subject. They wished they hadn’t brought it up. They should have known better.

‘Hitler stared straight through me,’ said Gerhard. ‘An unknowable distance. I was convinced then.’

In the kitchen, Catharina’s pile of dirty plates and cutlery suddenly felt leaden.

‘I was convinced then,’ repeated Gerhard. ‘Hitler was a man of honourable intentions. I saw his wonderful side and no one can take that away from me.’

Karl and Jana did not know what to think.

In the kitchen Catharina mechanically prepared a modest dessert of peaches and milk. Gerhard poured himself another drink.

Chapter Two

Michael came around every Thursday.

Jozef soon worked out the weekly visits were timed to avoid his mother, who had choir practice that evening in town. She often did not return until late after enjoying some gossip with the other singers. She knew Michael came. It was no secret. Occasionally the pair surprised each other on opposing paths in the Diederich’s doorway. Michael managed those moments best, politely greeting Catharina, who quickly returned the compliment, but who avoided eye contact and hastily escaped his more confident presence. Gerhard was always pleased to see Michael. They hugged like old friends, but Jozef did not know where from.

Michael sported round spectacles, like a teacher who had taught for 1,000 years. He always brought Jozef one glass bottle of Coca-Cola and one bar of chocolate. Jozef suspected it was an act of bribery, but he did not care. Michael seemed kind.

Michael and Gerhard talked non-stop those evenings in the Diederich’s front room, accompanied by the wireless and savouring Gerhard’s best whisky. Jozef noticed his father only shared his most expensive liquor with Michael. Even at Christmas, the cheap bottle came out for close relatives.

The pair smoked cigarettes but less than they drank. Still, by the end of the evening the space was filled with a fog echoing Bavaria in the Middle Ages. Jozef sat respectfully apart, but he loved inhaling the rare clouds that floated his way and experiencing the rushes of nicotine. The men often became quite drunk, but Michael always retained a certain style and certain quality. Michael never appeared drunk and Jozef had never witnessed him lose his calm, warm demeanour, unlike his father, who could quickly become ill-tempered and emotional when inebriated.

‘How are things Jozef? And how is school?’ Michael asked this evening. He was standing over Jozef in the doorway, with his hand resting protectively on top of his shoulder.

Jozef felt its power. ‘Gut Michael. Danke,’ he said, remaining on his best behaviour.

‘Herr Drescher to you, young man,’ warned his father.

‘Gerhard, we are all equals here this evening,’ corrected Michael and Gerhard did not argue.

‘And how is school Jozef?’ Michael repeated, leading the three of them through to the Diederich’s neat but modest front room, taking off his coat and expensive scarf and placing them on the side of the armchair he always favoured.

‘Gut danke Herr Drescher,’ Jozef remembered.

Gerhard had two generous glasses of whisky poured and waiting on a beaten and faded coffee table. The decanter of alcohol breathed in air at its centre. Jozef felt he could say anything on these occasions.

‘If you are ever in trouble at school, you must tell your father, promise me that,’ said Michael. ‘You are special, Jozef.’

The next morning, the first snow of the winter blanketed Munich, pure and thick. Every crunching step was like devouring the world’s most divine potato chip, thought Jozef, plotting a path to Sebastian’s house and then school.

‘Jozef!’ cried Sebastian, sprinting out his front door.

Jozef had only a moment to glance up before a snowball thudded against his breast. He immediately bent down to make and hurl one himself. The two friends clanged happily into one another like pots and pans on the path leading up the hill from Sebastian’s house. The snow had brightened everyone’s outlook. Ruined, bombed houses looked elegant even in white, like Hitler had never happened for a day.

Jozef went overboard and shoulder charged Sebastian, bowling his companion over into someone’s front garden. Sebastian picked himself up from the now flawed carpet, but not without first making a snowball to fire back in retaliation.

‘Get off my fucking lawn!’ complained a voice.

Jozef and Sebastian froze and despite the breathless chill flushed hot. The top half of an unkempt man, unshaven and topless but for a grubby white vest, was poking out the front door, only a few yards from the boys. They turned and desperately ran and ran until they felt safe again and began laughing.

‘What an arse!’ said Jozef.

‘I know!’ said Sebastian. ‘What’s wrong with him?’

* * *

Jozef and Sebastian both had double German first thing that day in school. It flew by and carried them all the way to the mid-morning break. Herr Slupski took it and was something of a maverick and their favourite teacher at school by far. Pupils vied for his attention and they cherished every word when they came their way. When he spoke to them, they felt like they were the only child in Bavaria. They were currently reading Animal Farm – A Fairy Story by George Orwell, but they were quickly discovering it had nothing to do with either animals or fairies.

‘All power corrupts,’ declared Herr Slupski to the class following the opening chapters.

He read books out loud and everyone followed. There were set chapters to read at home to accelerate the story, but few actually read them. Jozef, however, consumed them religiously. He was disappointed when there were no more pages to work through.

The pupils wrote short stories, often about anything they liked and Herr Slupski marked them out of twenty. They were now in their second year at secondary school and Jozef had not yet beat a sixteen. But then only two boys, one of them maddeningly Sebastian, had received a seventeen. Jozef bitterly lamented that fact. He poured his emotions into his pieces, but often languished on fourteens or fifteens.

‘Your use of language is to be applauded,’ Herr Slupski said to Jozef, who adored the attention but who equally deplored the critique. ‘But at times it is incongruous. It does not work. You are forcing words, Jozef.’

Jozef did not listen. He simply continued to look up long words he did not fully understand and shoehorned them into his narratives. He was always

hugely impressed with himself – until he saw ‘fifteen’ scrawled beneath his latest creation in Herr Slupski’s unmistakeable hand. Jozef woke early every other Sunday to write his German essays. They were set once a fortnight on Fridays to be handed in on Tuesdays. Jozef always had his done by mid-Sunday morning. Sebastian typically wrote his at the eleventh hour and refused Jozef’s exasperated pleas to socialise that night. They did not otherwise spend many evenings apart.

‘There are only two chapters left in Animal Farm,’ Herr Slupski announced at the end of their lesson.

Thin, grey hair was artfully swept over to one side and thick black glasses framed his face. He wore tweed suits and dressed less conventionally than Jozef’s other teachers, who were careful to keep their distance. Herr Slupski did not seem to mind. Other teachers seemed desperate to be liked by the pupils, who in turn smelt blood and subsequently preyed on them with ruthless efficiency.

Herr Slupski had begun ruling first by fear and then garnered begrudging respect before earning their unconditional love, which he now returned in spades. However, if anyone dared step out of line he instantly regressed to the furious dictator who had marched up and down the classroom those first few weeks and who had screamed, ‘Hitler was a bastard!’ one shocking day.

Jozef and, for once, Sebastian were hungry to get home that night and enjoy the end of Animal Farm. They had been gripped by the latest pages in class.

A Quiet Genocide

A Quiet Genocide